Nejnovější

Nejčtenější

- Václav Klaus hostem v podcastu Insider: Druhý den po volbách jsem pochopil, že je konec

- Pondělní glosa Jiřího Weigla: Amok

- Ivo Strejček: Důsledky války s Íránem mohou být pro Západ velmi zlé

- Ivo Strejček: Za Ukrajinu? Kdepak, jen další protivládní demonstrace

- Václav Klaus v pořadu Napřímo na TN Live

Hlavní strana » English Pages » Speech of the President at…

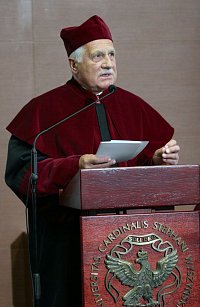

Speech of the President at the Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University

English Pages, 11. 10. 2012

Mr. Rector, Professors, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen,

Mr. Rector, Professors, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure to be here and a great honour to receive the honorary doctorate from your University.

As a politician, as President of the Czech Republic who is on an official state visit to your country and as a professor at the Prague School of Economics, I am aware of the importance of academic institutions and universities. It is my world. That is the main reason why I so highly appreciate the opportunity to address such esteemed academic audience. I follow with great interest the stances and values your University stands for and I am aware of the role Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński played in the history of your country.

I take the doctoral degree of your University as a personal award which reflects my political and academic activities, and also as an extraordinary and friendly gesture towards my country, the Czech Republic, for which Poland is not only a neighbour with similar historical experiences but also a country with which we have many things in common. The positive development of the Czech-Polish and Polish-Czech relations has always belonged to my political priorities and I would like to express my gratitude to your Academic Senate and to you, Mr Rector, for having recognized this fact.

I looked very carefully at the four points containing your arguments for honouring me with this very high academic award and was pleased to see that you touched on my main fields of interest and efforts. It gives me a good feeling that my endeavour was not fully useless and that my activity has some following even in your country.

I don’t intend to repeat here my standard topics today which are discussed in three books published in your country:

- Błękitna planeta w zielonych okowach

- Czym jest Europeizm?

- Gdzie zaczyna się jutro.

Let me use this opportunity for something else, for sharing with you some of my worries I feel when I look at the world around me twenty three years after the fall of communism. This brings me to Cardinal Wyszyński.

He was a personality with great courage who consistently resisted all kinds of attacks on human freedom and dignity. He helped the Poles not to lose hope in difficult times. The topics I would like to deal briefly with are to some respect related to the same or similar problem. Cardinal Wyszyński lived in an era of explicit absence of freedom, today we live in an era of many implicit attacks on our freedom.

For someone like me, who actively participated in preparing and organising radical political and economic changes in my country, the world we are living in now is a disappointment. I know that this is a very strong statement but I have to make it. It seems to me that we live in a far more socialist, centralistic, etatist, less free and less democratic society than I had then imagined. After a promising beginning, we are in many ways returning to the era we used to live in and which we had thought was gone once and for all. Let me make it clear that I do not speak about my or your country but about Europe and the whole Western world.

Two decades ago, it seemed to me that a far-reaching shift was taking place on the ‘oppresion versus freedom’ and the ‘state versus market’ axis right in front of our eyes. It was a justified feeling, but we had probably erroneously assumed that these changes were irreversible.

Today, many of us no longer have this feeling; at least I certainly do not. Once again, almost invisibly and in silence, capitalism and freedom have been weakened. It looked differently in the first years. The system of political freedom and parliamentary democracy was established quickly, thus replacing the former authoritarian or totalitarian political regime; the market and private ownership had started to dominate the economy; overall liberalisation, deregulation and de-subsidisation was taking place. The state radically receded in all its roles and the free individual got to the forefront.

People like me believed in the power of the principles of free society, of free markets, and of the ideas of freedom – as well as in our ability to promote these ideas. Today, at the beginning of the second decade of the twenty-first century, my feelings are different. I ask myself: Did I have unreasonable and unjustified illusions? Did I perceive the world in a wrong way? Was I naive or foolish? Were my expectations mistaken?

These questions deserve serious answers and I can’t aspire to give them on this occasion, in this very short speech. Nevertheless, I would like to start by saying that our expectations might have been wrong, but I do believe that it was not because we were under any illusions about the West.

We saw a number of problematic and the future endangering tendencies already then, and thanks to our life under communism, we – at least some of us – saw them more clearly than some of our friends in the West, including those who shared the same political and ideological views:

1. Some of us were unhappy having realized that socialism (or social-democratism, or “die soziale Marktwirtschaft”) was so deeply rooted in the Western society.

2. Since the 1960s and 1970s, when the Club of Rome began to formulate its first reports, I have been afraid of the green ideology, in which I saw a dangerous alternative to the traditional socialist doctrine. In my eyes it represented a very radical attempt to change human society and to weaken its freedom and prosperity.

3. People like me were always aware of the leftism of intellectuals, having seen that the vast majority of them were the driving force behind communism. Already at that time, I followed with great concern the ‘excessive production of undereducated intellectuals’ who emerged in the West as a result of the rising university education for all. One of its implications is that the superficiality of public discourse has reached extraordinary dimensions.

4. Socialism (or rather communism, as we say today) has from its very beginning been based on an apotheosis of science and on a firmly rooted hope that science is able to solve all existing human and social problems, which is why it is not necessary to change the system. It suffices to make it slightly more enlightened. Our communist experience tells us convincingly that the superstition that social problems can be solved by social science is a tragic misunderstanding.

These were the issues I was already then aware of but there are other problematic issues – as we see them now – that people like me underestimated or did not see at all.

1. We probably did not fully understand the far-reaching implications of the 1960s. This was a moment of the radical denial of the authority of traditional values and social institutions. As a result, generations were born that do not understand the meaning of our civilisational, cultural and ethical heritage, and are deprived of a moral compass guiding their behaviour.

2. I feared – but insufficiently – the gradual shifting away from civil rights to human rights. I did not see the power of the ideology of human-rightism and did not anticipate the consequences of it. Human-rightism has nothing in common with practical issues of individual freedom and free political discourse. It is about entitlements, claims, positive discrimination and political correctness.

3. Related to human-rightism and political correctness is the massive advancement of another contemporary alternative or substitute for democracy, juristocracy. Every day we witness political power being taken away from elected politicians and moved to unelected judges. All that is a part of an illusion about potential (and desirable) abolition of politics, in other words, of democracy.

4. Likewise, I did not expect the position NGOs (all kinds of the so called civil society institutions) would gain such power in our countries (and particularly in the supranational world) and how irreconcilable their fight with parliamentary democracy and with our freedom would be. It is a fight that they are winning more and more as time goes by.

5. We used to live in a world of suppressed freedom of the press for too long and that is why we considered the unlimited freedom of the media as a prerequisite for a truly free society. Nowadays I am not so sure about it. Formally, in our countries, as well as in the whole Western world, there is an almost absolute freedom of the press, but at the same time an unbelievable manipulation by the press. Our democracy changed into mediocracy, which is yet another alternative to democracy, or rather one of the ways to destroy it.

6. In a closed or semiclosed communist world we failed to see the danger of the gradually ongoing shift from national and international to transnational and supranational in the current world. In those days we did not follow European integration closely enough. We tended to see only its liberalizing aspect rather than its contribution to the creation of a post-political society that destroys the democracy and sovereignty of countries.

7. I did not expect such a weak defence of the ideas of capitalism, free market, and minimal state. I did not imagine that capitalism and the free market would become almost inappropriate, politically incorrect words that a ‘decent’ contemporary politician should better avoid.

8. I did not expect such popularity of public goods, of the public sector, of the visible hand of the state, of redistribution. I did not expect that the ideas of Adam Smith, Friedrich von Hayek and Milton Friedman would be so quickly abandoned; that people would so quickly forget that regulation is yet another expression for planning; that social policy would not differ much from communism; that after a radical removal of grants and subsidies of all kinds we would be – by means of a new re-subsidisation of the economy – once again forced to introduce them; and that such mistakes would be made in the economic policy. I did not expect that people would be so unwilling to take on the responsibility for their lives, that there would be such fear of freedom, and that there would be such trust in the omnipotence of the state.

This is just a brief outline of my views on all that. What I would like to stress is that we have to resist it, especially here in the academic sphere, that we have to do our best to keep universities as fortresses of free thinking, of free, not politically correct speech, of respect to opposing views, of merciless criticism of untruth, of hypocrisy, of manipulations we are so often confronted with in our contemporary world.

I wish your University much success in this battle of ideas and once again, thank you for the award you honoured me with.

Václav Klaus, Warsaw, 11 October 2012

- hlavní stránka

- životopis

- tisková sdělení

- fotogalerie

- Články a eseje

- Ekonomické texty

- Projevy a vystoupení

- Rozhovory

- Dokumenty

- Co Klaus neřekl

- Excerpta z četby

- Jinýma očima

- Komentáře IVK

- zajímavé odkazy

- English Pages

- Deutsche Seiten

- Pagine Italiane

- Pages Françaises

- Русский Сайт

- Polskie Strony

- kalendář

- knihy

- RSS

Copyright © 2010, Václav Klaus. Všechna práva vyhrazena. Bez předchozího písemného souhlasu není dovoleno další publikování, distribuce nebo tisk materiálů zveřejněných na tomto serveru.