Nejnovější

- Václav Klaus pro Lidové noviny o své nové knize „Dílčí reformy jsou málo, řešením je systémová změna“

- Páteční glosa IVK: Podceňovaná negativní stránka digitalizace

- Přání Václava Klause k 90. narozeninám Jana Klusáka

- Václav Klaus na CNN Prima News o své nové knize "Dílčí reformy jsou málo, řešením je systémová změna"

- Václav Klaus ve 50. díle pořadu XTV: Pane prezidente!

Nejčtenější

- Milan Knížák: Injekce pro Ameriku

- Václav Klaus představil svou studii k potřebě systémové změny české ekonomiky

- Václav Klaus k vítězství Petera Pellegriniho v prezidentských volbách na Slovensku

- Václav Klaus: Dílčí reformy jsou málo – řešením je systémová změna

- Jiří Weigl: Slovenské volby a česká politika

Hlavní strana » English Pages » The Euro as a Non-Optimum…

The Euro as a Non-Optimum Currency Area

English Pages, 2. 6. 2010

After the fall of communism, the Czech Republic wanted to be as soon as possible a normal European country again, after being excluded from participating in the post-WW2 European integration process for 41 years. The only possibility to achieve this was to become a member country of the EU. We had no other choice but the communist experience was still too “fresh”. We wanted to be free and didn’t want to loose our freedom and the finally regained sovereignty. Since the very beginning, many of us were therefore in favor of a looser form of European integration, against the so called deepening of the EU and against the creation of political union in Europe. People like me very early understood that the idea of European single currency is a dangerous project which will either bring big problems or will lead to undemocratic centralization of Europe. My position was clear: with all my reservations, we had to apply for EU membership but at the same time we had to fight against projects such as the euro.

With all of that in mind and as a long-standing critic of the idea of a European single currency (based on my economic background), I have not rejoiced at the current problems in the eurozone because their consequences could be serious for all of us in Europe –for members and non-members of the eurozone, for its supporters and its opponents. Even the enthusiastic propagandists of the euro suddenly speak about the potential collapse of the whole project now and it is us who say we have to look at it in a more structured way.

The term “collapse” has at least two meanings. The first is that the eurozone project has not succeeded in delivering the positive effects that had been rightly or wrongly expected from it. It was mistakenly and irresponsibly presented as an undisputable economic benefit to all the countries willing to give up their own “long treasured” currencies. Extensive studies that were published prior to the launch of the European single currency promised that the euro would help to accelerate economic growth and reduce inflation and stressed, in particular, that the member states of the eurozone would be protected against all kinds of external economic disruptions (the so-called exogenous shocks).

It is quite evident that this has not happened. After the establishment of the eurozone, the economic growth of its member states had even slowed down compared to the previous decades, thus increasing the gap between the rate of growth in the eurozone countries and that in other major economies – such as the United States and China, smaller economies in Southeast Asia and other parts of the developing world, as well as Central and Eastern European countries that are not members of the eurozone.

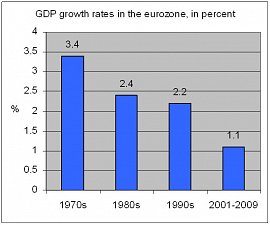

Economic growth in Europe has been slowing down since the 1960s thanks to the more and more damaging economic and social system which started dominating Europe at that time. The European “soziale Marktwirtschaft” is an unproductive variant of a welfare state, of state paternalism, of “leisure” society, of high taxes and low motivation to work. The existence of the euro has not reversed that trend. According to the European Central Bank, the average annual rate of growth in the eurozone countries was 3.4% in the 1970s, 2.4% in the 1980s, 2.2% in the 1990s and only 1.1% from 2001 to 2009 (the decade of the euro). A similar slowdown has not occurred anywhere else in the world (speaking about “normal” countries, e.g. countries without wars or revolutions).

Economic growth in Europe has been slowing down since the 1960s thanks to the more and more damaging economic and social system which started dominating Europe at that time. The European “soziale Marktwirtschaft” is an unproductive variant of a welfare state, of state paternalism, of “leisure” society, of high taxes and low motivation to work. The existence of the euro has not reversed that trend. According to the European Central Bank, the average annual rate of growth in the eurozone countries was 3.4% in the 1970s, 2.4% in the 1980s, 2.2% in the 1990s and only 1.1% from 2001 to 2009 (the decade of the euro). A similar slowdown has not occurred anywhere else in the world (speaking about “normal” countries, e.g. countries without wars or revolutions).

Not even the expected convergence of the inflation rates has taken place. Two distinct groups have formed within the eurozone – one (including most of the countries of western and northern Europe, behaving like Germany) with a low inflation rate and one (including Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland) with a higher inflation rate. We have also seen an increase in long-term trade imbalances. There are countries where exports exceed imports and countries that lastingly import more than they export. It is no coincidence that the latter countries also have higher inflation. It has no connection with the world-wide crisis. This crisis “only” escalated and exposed long-time hidden economic problems, it did not cause them.

During its first 10 years, the eurozone has not led to any measurable homogenization of its member states’ economies. The eurozone, which comprises 16 European countries, is not an “optimum currency area” as defined by the economic theory. We all know that. Even the former member of the Executive Board and Chief Economist of the European Central Bank Otmar Issing has repeatedly pointed out (most recently in a speech in Prague in December 2009) that the establishment of the eurozone was primarily a political, not an economic, decision. In such a situation, it is inevitable that the costs of establishing and maintaining it exceed its benefits.

My choice of the words “establishing” and “maintaining” is not accidental. Most economic commentators were satisfied by the ease and apparent inexpensiveness of the first step (the establishment of the common monetary area). This helped to form the impression that everything was fine with this project, which was a mistake at least some of us have been pointing out even before the existence of the euro.

The exchange rates of the countries joining the eurozone probably more or less reflected the economic reality at the time when the euro was born. However, over the last decade, the economic performance of eurozone countries diverged and the negative effects of the “straight-jacket” of a single currency have become more and more visible. When “good weather” (in the economic sense of the word) prevailed, no visible problems arose. Once the crisis (or “bad weather”) arrived, the lack of homogeneity manifested itself very clearly. In that sense, I dare say that – as a project that promised to be of considerable economic benefit to its members – the eurozone has failed.

Another issue is the possible collapse of the eurozone as an institution, the demise of the euro. To that question, my answer is no, it will not collapse. So much political capital had been invested in its existence and in its role as a “cement” that binds the EU on its way to supra-nationality that in the foreseeable future the euro will surely not be abandoned.

It will continue, but at a very high price – the low economic growth. It will bring economic losses even to the non-members of the eurozone, like the Czech Republic.

The huge amount of money that Greece will receive can be divided by the number of the eurozone inhabitants and each person can calculate his or her own “contribution”. However, the “opportunity” costs arising from a loss of a potentially higher growth rate, which is much more difficult for a non-economist to imagine, will be far more painful. Yet, I do not doubt that for political reasons this price will be paid and that the eurozone inhabitants will never find out just how much the euro truly cost them.

To summarize, the European monetary union is not at risk of being abolished. The mechanism that will save it is the increasing volume of financial transfers that will have to be sent to eurozone countries suffering from the biggest economic and financial problems. Yet, everyone knows that sending massive financial transfers is possible only in a state and the EU, or the eurozone, is not a state. Only in a state there is a sufficient feeling of solidarity among its citizens. Only in a state – and the unified Germany in the 1990s is an excellent example – can massive financial transfers be justified and made politically viable. (By the way, the inter-German financial transfers in that era annually equaled the whole sum potentially needed for Greece to survive). Twenty years ago, I happened to be the minister of finance in a dissolving political – and monetary – union called Czechoslovakia. I have to confess that the country broke up because of the lack of mutual solidarity.

That is why Europe will have to decide whether to centralize itself politically as well. Europeans don’t want that because they know (or at least feel) that it would be to the detriment of liberty and prosperity. There is, however, a real danger that the politicians will do it anyway – behind the backs of those who elected them. And this is what bothers me most. The recent dealings in EU headquarters in Brussels – literally behind the closed doors – about the aid package for Greece demonstrated that there is no democracy there. The German-French tandem made the decision on behalf of the rest of the eurozone countries and I am afraid this will continue.

It is evident that the euro – the European single currency – and the currently proposed measures to save the euro do not represent any “salvation” for the European economy. In the long run, it can be saved only by radical restructuring of the European economic and social system. My country made a velvet revolution and a radical transformation of its political, economic and social structure. Fifteen years ago, I was sometimes joking that after entering the EU we should start a velvet revolution there as well. Unfortunately, this ceases to be a joke now.

The Czech Republic has not made a mistake by avoiding the membership in the eurozone. I am glad we are not the only country taking that view. On April 13, the Financial Times published an article by the late Governor of the Polish Central Bank Slawomir Skrzypek. He wrote it shortly before his tragic death in the airplane crash near Smolensk, Russia. In that article, Skrzypek wrote, “As a non-member of the euro, Poland has been able to profit from flexibility of the zloty exchange rate in a way that has helped growth and lowered the current account deficit without importing inflation.” He added that “the decade-long story of peripheral euro members drastically losing competitiveness has been a salutary lesson.” There is no need to add anything to that.

Václav Klaus, Wall Street Journal online, June 1, 2010

- hlavní stránka

- životopis

- tisková sdělení

- fotogalerie

- Články a eseje

- Ekonomické texty

- Projevy a vystoupení

- Rozhovory

- Dokumenty

- Co Klaus neřekl

- Excerpta z četby

- Jinýma očima

- Komentáře IVK

- zajímavé odkazy

- English Pages

- Deutsche Seiten

- Pagine Italiane

- Pages Françaises

- Русский Сайт

- Polskie Strony

- kalendář

- knihy

- RSS

Copyright © 2010, Václav Klaus. Všechna práva vyhrazena. Bez předchozího písemného souhlasu není dovoleno další publikování, distribuce nebo tisk materiálů zveřejněných na tomto serveru.